Entre Nous with Joy Press

by

Marcelle Karp

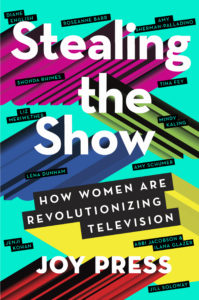

Joy Press and I have been friends a long, long time. Before kids. Before mortgages. Before marriages. We met in the years when Third Wave Feminists were writing their legacy, going to see Bikini Kill and Bratmobile, always the girls in the front. Joy Press was my first friend to write a book, “The Sex Revolts: Gender, Rebellion, and Rock’N’Roll,” which she co-wrote with her husband, Simon Reynolds. Over the years, Joy has been embedded in pop culture, with a storied career as the chief television critic at the Village Voice, entertainment editor at Salon, as well as the Los Angeles Times. She’s just released her second book, Stealing The Show: How Women Are Revolutionizing Television, about how Abbi Jacobson & Ilana Glazer, Amy Schumer, Amy Sherman-Palladino, Diane English, Jenji Kohan, Jill Soloway, Lena Dunham, Liz Meriwether, Mindy Kaling, Roseanne Bar, Shonda Rhimes, and Tina Fey are turning the world on with more than just their smile.

This is the first time I’ve interviewed you.

I did a girl power piece a million years ago when we first knew each other, I think I interviewed you for that.

Grrl power? Yes, that would make sense, why you’d interview me. So, let’s talk about Stealing The Show. I like how embedded in contemporary television culture it is.

I would have liked to have spent more time on the history because its really fun to go back in the archives. I decided it would really focus more on contemporary television and the path to where we are now. I picked a point intuitively that felt like a beginning moment: Murphy Brown and Roseanne starting within a month of each other, and starting in the throes of what came to be called the culture wars in the late 80s and early 90s. When I started [writing the book] in 2015, they seemed like kind of forgotten inspirations for a lot of what women were doing today on television. Of course, after I finished the book, they announced that they were rebooting first Roseanne and then Murphy Brown so it seems like I was psychic.

You might have a future as a crystal ball magician.

Not really. When I started I thought we were going to have a woman president!

Can you unpack the culture wars?

The early one? Not the one we’re in right now?

Right. The earlier one.

The book starts in 1988. Murphy Brown and Roseanne premiered in the fall of 1988, a month apart from each other. America was in the middle of what came to be called as the “culture wars.” It was Reagan going into Bush Senior, the rise of the religious right; this conservative political culture in America that was very much on the offense of women’s rights, women’s reproductive rights, affirmative action, gay rights.

That sounds very much like we’re going through now.

Right. There was a very very strong conservative impulse. It really crystallized around these characters —Murphy Brown and Roseanne—because even those they are very different characters, they epitomized a lot of things that really repulsed the right wing. Particularly Murphy Brown. The Vice President of America, Dan Quayle, actually decided to use the fictional character of Murphy Brown—who was in the show, a single working woman, who was the anchor of a television news program, a very aggressive, truth seeking reporter who took no bullshit from anyone and broke all the rules and during the course of the show, got pregnant and decided to raise the baby on her ow—and went on the attack against her. He said she was what was wrong with America, she was the kind of person that was destroying the American family and rather than backing off, he made it the center of the Bush/Quayle presidential re-election campaign against Bill Clinton. This really ended up pitting the right wing of America against Hollywood, and against the left and that’s where the idea of the Hollywood elite came from. It was a very strange moment because this really was a fictional television character. Of course, it didn’t turn out well for them—Bill Clinton won.

And yet, they persist, these conservatives.

When I was writing those chapters, I was really fascinated because that moment was so extreme. The country was so polarized. It was the beginning of the conversation about red states and blue states and the religious right was very much in the ascendant. Arts funding was embattled. There was an attack on science and birth control and abortion and gay rights and affirmative action. When I started the book it felt like, this is in the past, we’re about to have a female president. I hadn’t finished the book when the election happened and I was horrified because I started realizing the language of the Trump administration and the Republicans and the bills that were being discussed were so similar to the things I had just been reading about in this late 80s/early 90s period. That was really striking, realizing we were back in a very similar culture war, in a very similar backlash. Breitbart was regularly covering every thing Lena Dunham did and Amy Schumer did, at least in part because they had been Hillary Clinton supporters. But also they were also these very outrageous women who were kind of disturbing to the same kind of right wing vanguard as had been in the culture wars of the late 80s and early 90s.

And women being the target of the outrage, of the stirring of the embers.

It feels very important to me. I wanted to really get across both a sense of the women who were making these shows and the shows themselves. I also felt it was really important to thread political context and cultural context because these shows aren’t happening in a vacuum; the absence of certain kinds of characters and visions on television means something. I don’t think there’s a direct correlation necessarily between a tv show and its moment but I certainly think that television is very much shaped by the political forces and the cultural forces. Orange Is The New Black in its own way is very much interacting with the culture. Transparent is very much interacting with the culture. Broad City is sort of reacting to the culture and creating an imaginary space that doesn’t exist on television otherwise.

A lot of the women, although not all of them, had other projects before running their own shows.

I talk about Weeds, which was Jenji Kohan’s show before Orange Is The New Black. That’s one that I think is really important but has been forgotten to some degree. Weeds is very important to Showtime and their attempt to go head-to-head with HBO in terms of original programming. They used it to kick off a string of shows that were kind of driven by female creators and had kind female leads like Nurse Jackie, The C-Word. And The United States of Tara which Diablo Cody did and Jill Soloway worked on. And of course, there was The L Word. It felt like they used those shows about middle aged women who were kind of on the edge almost to compete with the macho HBO Sopranos line up. Jeni Kohan struggled, even though she had this ground breaking show, to get someone to pick up Orange Is The New Black. There is this strange shadow history of women in television which I hadn’t seen it told.

And now we’re seeing stories unfold on television, with women front and center, behind the scenes and in front of the camera, often putting themselves in these lead roles, as we’re seeing with Smilf and Fleabag.

By the time I was finishing the book, there were so many different iterations—SMILF, Fleabag, Insecure, Queen Sugar, Crazy Ex Girlfriend. There has been an explosion. It’s an inspiration.

In researching the trajectories of the careers of these women, is there anything that surprised you?

One thing stands out is how similar many experiences were, how many things echoed through time. The struggles that women had in 1988 and how we’re still having in it 2010 or 2012, how many women struggled with this idea of characters being likable or being too angry. I know that it is very difficult to get a tv show made and I know that great show runners have a hard time. There’s no promise for anyone that you’re gonna get your show made. But it is a very odd thing that if you have managed to establish yourself and created a really groundbreaking show to struggle. It was still surprising to me how many of these women struggled even after having proved themselves to get somebody to take a leap on their vision.

So there’s still so many more ideas left in a hard drive somewhere?

Almost every woman I talked to would tell me about some show along the way that sounded fantastic to me that didn’t get picked up. Maybe it didn’t get picked up because it just wasn’t there on the page, maybe it didn’t get picked up because it was just a bad fit with the executive who was in charge at that moment, maybe it was just bad timing. Jill Soloway was developing a show that was about sixties groupies in Laurel Canyon and Zoey Deschanel was loosely connected to it. I mean, what a great show! So yeah, the list of fantastic sounding things that never got off the drawing board is also really startling.

Why are women such a hard sell to executives in charge of delivering entertainment?

Well I think for me the question was how much is this just normal television and how much of this is either the networks didn’t know what to do with it, didn’t think they could sell it, or was personal taste. One of the things I heard over and over again was that executives were almost always pushing for more men. They generally didn’t like to have a female who was totally at the front and if they did, they’d surround her with men. Murphy Brown had a fantastic ensemble and there was one other woman who was quirky but it was an ensemble of men. You go to New Girl and the show is called New Girl but they basically surrounded her with men. It was made very clear to the creator Liz Meriwether that she needed to have guys. She had tried to do a series pre-New Girl that was all women and it didn’t get picked up.

And yet Sex and the City was a huge success.

Well, Sex And The City is a mystery because Sex And The City helped make HBO’s reputation. It’s this lone landmark that just sits out there in the desert. There was definitely an attempt by networks to follow up on Sex And The City, mostly not very good, directly trying to rip off that formula. Certainly a network couldn’t quite do it and then it just got left for dead. HBO never followed it. I would read the trades and I was constantly seeing the names of all these great female writers—writers of books, journalists, actresses, directors—who were supposed to be developing a show for HBO. At one point, I made a whole list of them. I checked in with HBO and none of them except for Girls ever happened. I think for the network model, a lot of it was about money and fear that women weren’t going to make them enough money.

And yet, on the streaming services and the cable networks, they could get away with having female centric shows.

A lot of the shows I talk about in my book actually happened outside the network system—Shonda Rhimes is a huge exception. And you do have people like Tina Fey who managed within the network system.

What makes a really good show actually make it off the page?

A really good show is magic. A million things have to come together for a show to be really great. You could have a fantastic writer but it just doesn’t gel. So all of these shows that you love happened because everything went right. Girls certainly wasn’t a huge ratings success but theres definitely something to be said about shows that get everyone what they call the chattering classes chattering. The comedy style of 30 rock was really important: Tina Fey as a smart, funny, nerdy woman who is both creating this show playing a tv writer on the show and also starring in it set a template that made it much easier for somebody like Mindy Kaling to come along and say I want to do my own show, I’m going to write it, I’m going to star in it. That created an important new kind of path that didn’t really exist before.

***

Follow Joy on Twitter, and buy Stealing The Show, now!

0 Comments